Some say software architects are those who should have answers to technical questions. I’d bet that’s true, but only if we accept some answers to be stupid. Still, having the knowledge to keep a decent smart-to-stupid-answer ratio is a good thing. A post from a series called "Mind the architect".

"Mind the architect" is a series of short articles about becoming an architect and how building the right mindset helps in that role.

My much more experienced colleague (hey David!), who is also an architect at Cognifide, noted a fascinating phenomenon he's constantly facing. And to be honest, we are all experiencing it too. One day you think you nailed some topic and you feel you finally got it right, just to find yourself next day to be a clueless child. Somehow the long awaited understanding goes with the wind. You realise there is still some magic inside that you haven't spotted, a step in a process you don’t understand, a variation you didn't know, etc.

Despite his many years of work as an architect and just a few of mine, we share the same observation. It proves that there is always something you don't know regardless of your mileage in the business. It’s like with the universe. Firstly, we still don't know how big it is. Secondly, if the theories are right, it expands at an increasing rate. The blend of technology and business that architects are dipped in, is like that universe. You may spend 10 years of learning the stuff to spot you actually know relatively less than when you started.

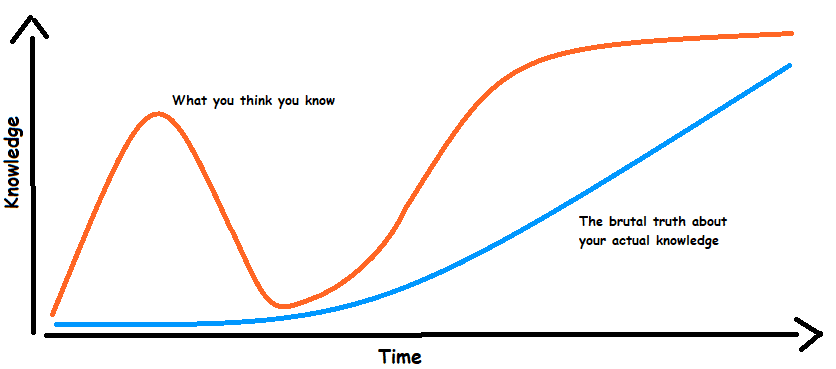

I guess many of you saw a chart like this one. A curve that visualizes the unobvious truth about our perception of knowledge. I love the fact how universal it is.

(pardon my handmade masterpiece ;) )

(pardon my handmade masterpiece ;) )

I found myself in that situation. And despite the fact that I'm, generally speaking, aware of my own incompetence in numerous aspects, when I changed my hat from a tech lead to architect, I thought I knew enough to be efficient in that role and progress at increased speed on my career path.

"You know nothing, Jon Snow" - some would say and today I second them.

The sooner you accept the fact, that promotion and role change is a step which moves you outside of the area you've been safely working in, the better. It's a new, much broader land to explore, with different challenges and situations to face. Past experience sometimes helps. Most of the times if you face the same challenge again. But it's much harder to apply lessons you learened to perfom tasks you have to do for the very first time. Respect for lack of knowledge, your own and among others, helps. You will find better to work with people who ask smart questions. Especially comparing to these guys who tend to state false claims based on their incorrect assumptions and shallow knowledge.

Another way of looking at this is to realise that we usually assess the level of our own knowledge incorrectly. There's actually a known research about that called The Dunning-Kruger effect. Even without conducting any case studies, it is quite common to observe that people without deep domain knowledge tend to put bold statements about their expertise. On the other hand, people who are actually experts, most of the times present themselves as still being on the learning curve. If you want to read more about this effect, you should take a look at the article The Dunning-Kruger effect in innovation.

So what to do with this? Nothing :) Accept the fact the knowledge is spread across multiple people, no one knows everything and it's natural to work with incomplete data.

How I try to help myself in such situations? I look for the people who say "I'm not an expert, but <smart question goes here>" as they are most likely to understand the stuff, enough to be helpful!

Hero image by Olivia Bauso, opens in a new window